Download your FREE ebook!

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment

What It Reveals About Hunger, Starvation, and Eating Disorders

As the world witnesses heartbreaking images emerging from Gaza today—where civilians endure siege, severe food shortages, and forced deprivation—the conversation about the consequences of hunger resurfaces. Starvation is not only a threat to life through illness and wasting; it leaves deep psychological scars on those who survive. To better understand its impact, history offers us a disturbing yet invaluable scientific case: the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, conducted during World War II. Though carried out eight decades ago on healthy volunteers, its lessons echo in today’s wars and in modern eating disorder clinics.

Background: Why This Study Was Conducted

Between 1944 and 1945, as World War II created famine conditions across Europe and Asia, millions faced severe hunger. The U.S. government funded a study at the University of Minnesota, led by physiologist Ancel Keys and psychologist Joseph Brozek. Their goal: to investigate how the human body and mind respond to prolonged food deprivation, and how best to rehabilitate survivors of famine.

Who Were the Participants?

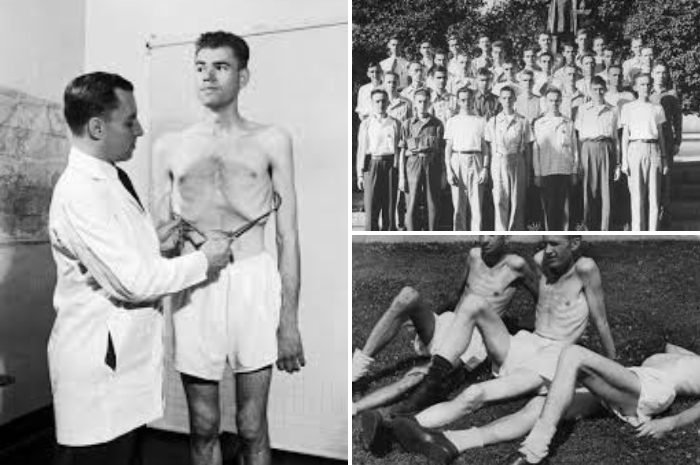

Thirty-six conscientious objectors—men who refused military combat service but volunteered for alternative civil service—agreed to take part. All were white males, aged 22–33, weighing on average 69 kg (152 lbs). Each completed psychological testing (the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, first published in 1943) before and during the experiment to measure changes in mood, behavior, and personality.

The Four Phases of the Experiment

1. Baseline Phase (12 Weeks)

For the first three months, participants ate a controlled 3,200-calorie diet to establish baseline measurements. Their weight, metabolism, heart rate, and psychological state were carefully recorded.

2. Starvation Phase (24 Weeks)

Calories were cut in half—to around 1,560 per day—consisting largely of potatoes, turnips, bread, and pasta. This diet was designed to mimic wartime Europe. Within weeks, the men experienced dramatic physical and psychological changes.

Physical Symptoms

- Resting heart rate dropped from an average of 55 to as low as 28 beats per minute.

• Hearts shrank by 17%; blood volume fell by 10%.

• Basal metabolic rate decreased by up to 50%.

• Extreme sensitivity to cold: participants layered clothing, lips and nails turned blue, and warm showers became daily highlights.

• Hair loss, brittle nails, thin wrinkled skin, anemia, dizziness, fainting, edema (fluid retention), constipation, slow wound healing.

• Sleep became fragmented, urination increased, and hearing improved oddly due to ear canal tissue shrinkage.

Psychological and Behavioral Symptoms

The men became obsessed with food—hoarding cookbooks, dreaming about meals, playing with food like children. Depression, anxiety, irritability, poor concentration, obsessive thoughts, social withdrawal, and even psychotic-like episodes appeared. Some reported nightmares about forbidden foods, guilt over imagined waste, and disturbing fantasies, including cannibalism. Sex drive plummeted. For many, food became the central and only focus of life.

Impact on Physical Activity

Exercise capacity collapsed. Harvard fitness tests showed a 72% decline. Simple tasks like walking or climbing stairs felt unbearable. Some participants even chose to walk in street gutters to avoid stepping up onto sidewalks.

3. Restricted Rehabilitation (12 Weeks)

After six months of starvation, men were divided into groups receiving modest calorie increases (400–1,600 extra daily calories). Recovery was painfully slow, and many continued losing weight. It became clear that 2,000 calories per day was insufficient for adult male recovery. Keys concluded that at least 4,000 calories daily for months were required to repair damaged tissue.

4. Unrestricted Rehabilitation (8 Weeks)

Finally, some men were allowed to eat freely. Intakes ranged from 4,400 to over 11,000 calories daily. They experienced relentless binge eating, gastric distress, and vomiting, yet still felt insatiably hungry. Weight rapidly returned, but disproportionately as fat—especially around the abdomen. For some, disordered eating persisted for years.

Long-Term Consequences

On average, participants lost 24% of their body weight during starvation. Most regained weight within 58 weeks, though many struggled with lingering binge urges, fear of food scarcity, and dissatisfaction with fat redistribution. Some reported altered relationships with food for life. Yet despite the trauma, the men went on to live productive lives—earning degrees, pursuing careers, and even receiving national honors.

Why the Minnesota Experiment Still Matters

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment is a cornerstone in understanding the devastating effects of famine and the psychological overlap with eating disorders. Its findings highlight how starvation reshapes both body and mind—knowledge that is tragically relevant today in conflict zones like Gaza, and in treatment centers worldwide.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

❓ What was the goal of the experiment?

➡️ To study the effects of semi-starvation and how to rehabilitate famine survivors.

❓ How many men took part?

➡️ 36 healthy male volunteers aged 22–33.

❓ What were the key findings?

➡️ Severe physical decline, psychological distress, food obsession, and slow recovery—even after refeeding.

❓ How is it relevant to eating disorders?

➡️ Many symptoms mirrored those of modern eating disorder patients, such as bingeing, obsession with food, and loss of social interest.

Sources

- 57-Year Follow-Up Investigation and Review of the Minnesota Study on Human Starvation and Its Relevance to Eating Disorders

- The Starvation Experiment – Duke Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences

- Seven Health (Real Health Radio Podcast)

- Wikipedia – Minnesota Starvation Experiment

This article was prepared by Sara Ibrahim for AnaArwa.com, to document one of history’s most significant medical experiments and connect it to today’s realities.

Leave A Comment